Why You Shouldn’t Reward Kids (And What to Do Instead)

If you want to motivate your child, giving rewards like stickers, toys, or money may not be the answer. Learn why you shouldn’t reward kids this way and what to do instead.

We rely on rewards a lot, don’t you think? We give kids candy for using the potty and toys for doing well in school. Teachers hand out “rock stars” that students can cash in for a prize.

But I’ve since learned that external rewards like these can sometimes do our kids a disservice. Yes, they might work in the short run, but over time, they lose their pizzazz or, worse, send the wrong message about what it means to make good choices.

Table of Contents

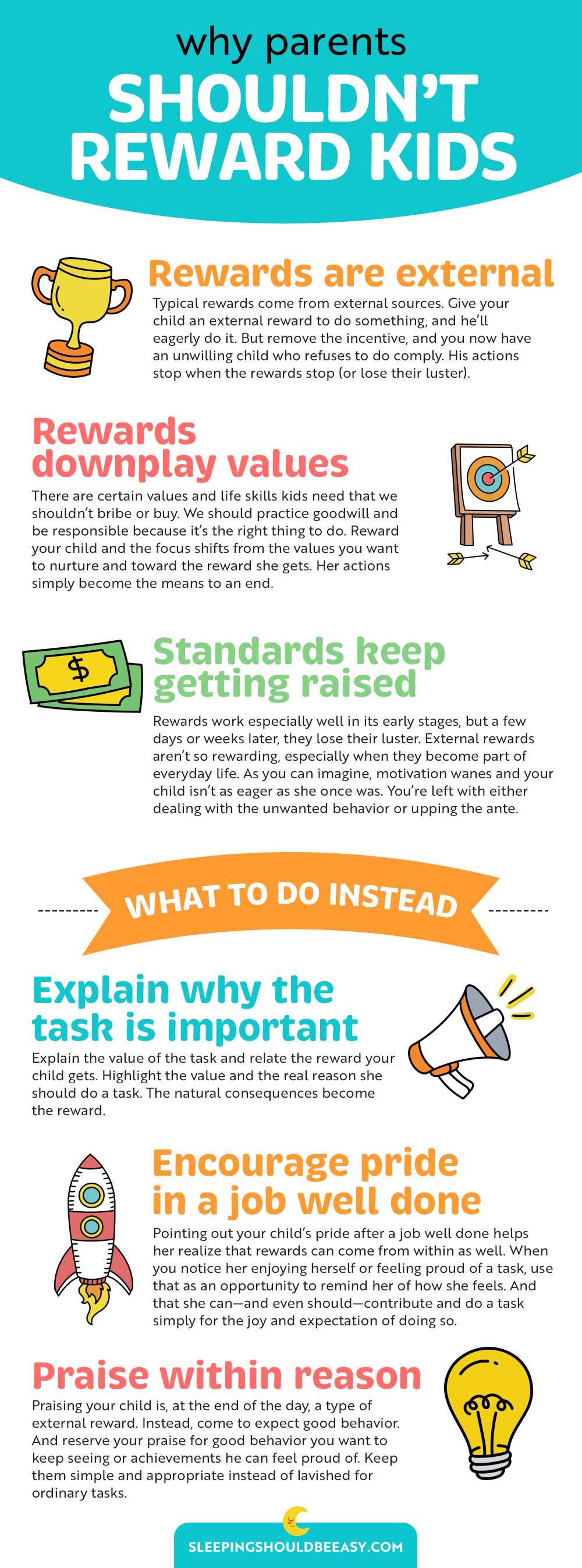

Why you shouldn’t reward kids

If the idea of giving your child a reward as a means to an end doesn’t sit well with you, you’re not alone. Check out the following reasons why you shouldn’t reward kids, followed by what to do instead:

Rewards are external

Typical rewards come from external sources. While this is fine in some circumstances (for instance, setting up a lemonade stand to earn money), many of the actions we’re trying to motivate kids to do should come from within.

Give your child an external reward to do something, and he’ll eagerly do it. But remove the incentive, and you now have an unwilling child who refuses to do chores or pee in the potty. His actions stop when the rewards stop (or lose their luster).

Instead, encourage intrinsic motivation. He cleans his room because of the pride he feels, the expectations he wants to meet, and even the standards he has set for himself—all without the promise of a typical reward.

After all, we want to raise hard working kids because they feel pride in their work, not for the chance to score a prize.

Free email challenge: Looking for actionable steps and quick wins in parenting? Join the Better Parenting 5-Day Challenge! This is your chance to challenge yourself and make the changes you’ve always wanted to make. Sign up today! You’ll also get my newsletters, which parents say they LOVE:

“Hi Nina, I would like to start by saying how much I love receiving your emails. They resonate with me so much. Through them I realize I’m not a perfect parent, nor will I ever be, but I try to do the best I can. Thank you for all the useful information.” -Monika Franczuk

Rewards downplay values

There are certain values and life skills kids need that we shouldn’t bribe or buy. We should practice goodwill and be responsible because it’s the right thing to do, no matter how indirect the rewards of doing so may be.

I don’t know about you, but I want my kids to grow up helping others willingly, and not with a “What’s in it for me?” mentality.

Rewards also extinguish a genuine love of learning. Reward your child for good grades and the focus shifts away from the values of learning and working hard and toward the reward she gets. Studying and reading simply become the means to an end.

At the end of the day, rewards don’t build values—at least the ones we want to nurture. We want kids to value a clean room, get along with their siblings, and be polite. We want them to be passionate about their interests and work hard to feel a sense of accomplishment. We don’t encourage those values when we only highlight the reward of a new toy or money for good grades.

Standards keep getting raised

Rewards work especially well in its early stages: Those stickers on the potty chart look awesome! That candy is so yummy! And that toy—I can’t wait to get more!

Except a few days or weeks later, those stickers lose their luster. The candy isn’t exciting anymore. Even the toy isn’t worth the trouble of sitting on the potty.

After a while, external rewards aren’t so… rewarding, especially when they become part of everyday life. As you can imagine, motivation wanes and your child isn’t as eager as she once was. You’re left with either dealing with the unwanted behavior or upping the ante.

Alternatives to typical rewards

Focusing too much on rewards can reap short-term benefits but at the cost of long-term habits and values. Offering rewards has its place, but perhaps not as often as you might think.

So, what can you do instead? If not rewards, what are your options? Thankfully, there are plenty of ways to motivate kids and get them to listen without typical rewards that are more effective and sustainable. Take a look at these alternatives:

Explain why the task is important

Let’s say your child isn’t being cooperative with returning her craft supplies to the storage box. You could see why—cleaning up isn’t exactly as fun as using them. But instead of offering a reward, explain the value of the task—and why it’s important.

“We put the craft supplies back into the box so that [we can find them easily later / we don’t step on them / your little sister won’t put them in her mouth].”

The focus is on a type of reward (she won’t lose the craft supplies), but not an external one (I get to eat a cookie). And the reward is related to the task (putting the supplies away means they won’t get stepped on). You’re highlighting the value and the real reason she should do the task. The natural consequences become the reward.

Encourage pride in a job well done

“You did it!” you can say to your child after she remembered to wash her hands after dinner. Pointing out her pride after a job well done helps her realize that rewards can come from within as well.

When you notice her enjoying herself or feeling proud of a task, use that as an opportunity to remind her of how she feels. She’ll remember that tasks don’t always need a bribe, especially when she draws a positive feeling from within.

And that she can—and even should—contribute and do a task simply for the joy and expectation of doing so. Just as the value of a task can serve as a reward, the pride in a job well done can do the same.

Praise within reason

Praising your child is, at the end of the day, a type of external reward. The last thing you want is for him to only do things if you’re there to praise him for doing so. Saying “Good job!” for every little thing can backfire and lose its intent when said too often.

Instead, come to expect good behavior. He’ll learn that he needs to brush his teeth even without his parents cheering him on. It’s just what we all do, a necessary task expected of everyone. Sure, you might’ve praised him when he was learning to brush his teeth, but it’s certainly not required after he has mastered the task.

If you’re wondering when it’s appropriate to praise him, rest assured it’ll come naturally. Feeling “forced” to praise him for brushing his teeth is likely overkill. But saying, “Yay, you did it!” when he rides his bike for the first time probably isn’t.

And reserve your praise for good behavior you want to keep seeing or achievements he can feel proud of. Acknowledge how happy he made his brother feel or that he can now go down the slide all by himself. Keep them simple and appropriate instead of lavished for ordinary tasks.

The bottom line

As with most things, moderation is key. Rewards have their place, but when used too often, they can have unwanted consequences, especially in the long run. Thankfully, you can apply other techniques to motivate your child or get her to listen instead of using rewards. She can make good choices—all without the promise of stickers or candy.

Get more tips:

- 7 Surprising Reasons Kids Need Responsibilities

- How to Teach Your Child Not to Show Off

- How to Teach Delayed Gratification in Children

- The Downsides of Having Too Many Toys

Don’t forget: Join my newsletter and sign up for the Better Parenting 5-Day Challenge below—at no cost to you: